Calf rearing farms, even the most modern ones, are genuine family businesses where the animals are loved and spoiled. Evert Verwoert’s farm in a village between the cities of Arnhem and Utrecht in the Netherlands called Opheusden, is no exception; and Evert is the perfect modern farmer. He has invested considerably and continues to do so wherever he feels there is room for improvement. He has two rearing units with a capacity for 1200 calves, and has automated and computerised as much as possible to rule out the risk of human error. The modern units are 30ft (10m) high with roofs that open and close automatically depending on the temperature and level of ventilation required inside the shed. On the east side of the sheds, the sunlight is filtered, because direct sunlight would generate too much heat in the summer. In the dark winter months, artificial lighting is left on until late into the evenings. Does it help the calves grow? No, but it does make it a more pleasant environment for them to live in.

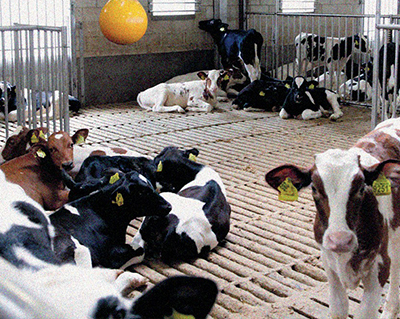

Evert has installed solar panels on the roof, which has turned his business into an energy neutral establishment. The reservoir for the manure under the stalls has enough capacity to store fourteen months’-worth, meaning he always has manure when he needs it. “My calves”, comments Evert “have a better quality of life than people in retirement homes.” The calves live in groups of ten and are remarkably quiet and relaxed as we walk around the stalls. They follow us and try to lick our hands. We can see a fresh supply of water for them to drink from, but what do they eat?

Evert takes us to the area where they prepare the feeding bins: tiled luxuriously and computerised of course. There is a large mixing basin filled with water at a temperature of 62°C/143°F. Outside, there are silos that dose the milk replacer powder into exactly the right quantities, straight into the basin. If necessary, the same system can be used weigh out nutritional supplements and minerals and mix with it with the rest. It takes four minutes to mix the milk replacer, then transport it to a storage tank and onwards, into a system of pipes in the pens. Each day, the calves are given 15g more formula milk than the day before. When it reaches them, it is exactly 42°C/107°F, and if a calf is unable to drink from a trough, Evert uses the floating teats waiting in the trough.

Evert likes to walk around the stalls, filling the troughs with a hose which is being fed to precision by his high-tech dosing system. Why does he walk around with a hose when he could automate that too? His answer: “A farmer should always be with his animals.

By feeding them myself, I know each and every calf, and they all know me”. Evert gives the calves more than just milk replacer. He has a strict regime that starts at 4:30 am with their first supply of milk. At 7:30 am he gives them a day’s supply of roughage and at 4:30 pm, they are given more milk. Having tasted the roughage, we can vouch that it tastes just as good to us as it does to the calves! It is a delicious mix of hay, various grains, corn, carob and even dried mandarin peel. The calves love Evert’s muesli. He demon- strates just how much by lifting a spoonful out of the bin. All of a sudden, the calves’ ears all stand on end and they start to moo very loudly in anticipation. Evert measures the roughage he feeds his calves accurately as well, using an electric cart that he had built for that very purpose.

Whilst all of this is going on, Evert has told us all about the process of calf rearing. The calves arrive when they are fourteen days old and receive a standard iron supple- ment. He puts the temperature up by 1.5°C in the rearing unit to help the calves settle down and the animals are moved in groups of ten into each pen. For the first three to four weeks, the calves are separated from one another by removable partitions, during which, Evert studies each of the animal’s behaviour. He gathers up any calves that appear weaker and puts them together in one pen so he can monitor them more easily. At this point, he introduces their daily routine and after twenty-seven weeks, they are ready for collection. The stalls are cleaned, disinfected, and prepared for the next calves that are due to arrive fourteen days later. Evert’s farm accepts only bull calves. They eat 10% more than heifers, but combining the two makes the whole process a lot more complicated.

Evert also shows us the office where he processes all of the data from each and every calf and saves it for five years. Every item of information down to the minutest of details is recorded, by the minute and by the gram: where the animals have come from, what they have been fed; medicines, diseases, visits from the vet; how they have been trans- ported; literally everything. Evert’s response: “most villages lose the odd resident occasion- ally, but I have never lost a calf!”

Calf rearing farms that are part of a wider supply chain are quite used to regular inspections and audits, often unannounced. Evert: “We are transparent about everything here. We have nothing to hide. That’s one of the reasons why I open the farm to the public.

I like letting people have a look around. It makes me feel proud. Of course there are some people who still have a negative perception of calf rearing, but that is simply ignorance. Anyone who rears calves will only be successful if he keeps healthy animals, and will do everything possible to keep them that way. Just look at my calves and how much they shine. They are better looked after here than those out there in the wild!”

Evert Verwoert was the first farmer in Europe to automate a farm to this extent. It is a magnificent farm and many farmers from around the world have come to visit him at his farm in the Netherlands. It is clear to see that he enjoys working with the animals, and that he enjoys life. The way he has structured his company means there is no need for him to work day and night. “I finish work at 6 o’clock in the evening so that we can lead a normal family life, including breakfast together in the mornings.”